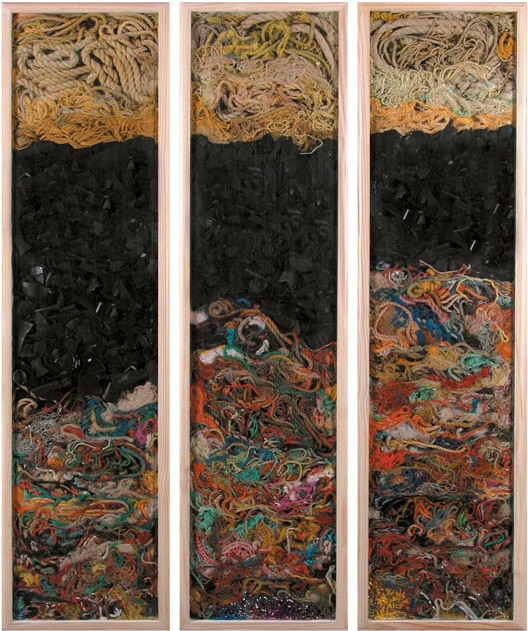

John Dahlsen “Black Lake”

Triptych 2003

165 cm x 44 cm each

JH: You have a great deal of success; travel all over the world, touring all over the world, doing different commissions and are continuing to create. Do you consider yourself successful?

JD: Well Jessica I’d have to start by saying I believe notions of success are very much relative. It’s like relative components. When someone says to me, I’ve done a big painting and I say oh really, what are the dimensions? and they say it’s about this by this, and I would say that’s a relatively small painting but then again there might be another painter who paints in miniature and to them that might be a large painting, as they normally create small size images.

It’s the same with any form of success. If you’re in a very localized area, like my home town of country Victoria, I might see myself as having success, and a lot of people that I know have said to me, “wow, you really made a mark as an Australian artist, who would have known”.

Within Australia I know I am also known, largely due to winning the Wynne prize of the Art Gallery of New South Wales. That put me on the main artistic stage.

I’ve been commissioned to do some large pieces, but then you have people like Andy Goldworthy, the environmental artist from Scotland. Now Andy, he’s achieved worldwide fame, you’ve got Keith Haring, you’ve got so many different artists that are almost household names. Damien Hirst, I think Damian has been very financially successful as well. I think he’s worth a billion dollars these days. His last show, he had 24 artworks, they were all valued at 1.4 million dollars and it was a sell out before the show even opened. Since then he’s created a lot of controversy as they were dot paintings and the Indigenous artists of Australia have said he’s been borrowing from their works. The’re accusing him of plagiarism and using their work. He’s saying that he didn’t actually get inspired by them he was also inspired by an American artist. So anyway the story goes on. I wanted to make this point that it’s all relative. In my mind I don’t see myself as being hugely famous or whatever or successful.

I’ve had different times in my life where I’ve been successful and then I’ve had times where its flatlined for a while. It’s a natural energy that these things take if you have had success. If you can ride out the times where nothing’s happening, that’s where you get your success. A lot of people fail that. A lot of people start abusing themselves, getting into drugs and alcohol or whatever it is they do. They stop staying fit, they stop eating good food, organic food, all that kind of stuff and they lose it. Success is when you can ride through that and that natural energy will take you up again. Then you might be asked to have another exhibition or you might be asked for another commission, whatever it is, because you just have that sort of energy.

So there’s a few, little bits of feedback about success.

JH: Did you come to realize you were a creator or an artist at quite a young age, I know you went to the Victorian College of the Arts in Melbourne, which is quite a renowned College, did you always know or did you come to find that you were going to be an artist over time?

JD: I kind of stumble into things. I never plan things out too much. When I was at secondary school I ended up creating a body of work. I think it had a continuous sort of flavor through it. It was a kind of surrealistic work that had my own individual input that made it unique. I developed that over a two year period during a time where I was quite sick and tired of the whole private boarding school kind of routine that I was in. I wasn’t interested in being a politician, or a sports star, or a lawyer, or a doctor like many other people aspired to at that institution. So I kind of locked myself away and became very internalized during the last 2 years there. I stumbled across a lady at the National Gallery of Victoria one day who said she was studying at the Victorian College of the Arts and the application time was coming up a couple of weeks later, when she heard I was just graduating with my HSC. She said why don’t you apply? and I didn’t even think about it, so I went inside and got the application forms and took them with me and actually documented the body of work, the whole surrealistic series that I did. Then 3 weeks later I was accepted for an interview. And then shortlisted. So I went there for the interview, it’s quite an institution. I think there were over 1,400 people applying or usually apply each year and only 23 got in, so you know it’s pretty hard to get in. I just took it in my stride, thinking “Ok, great I’m in”. I hadn’t even done my HSC exams and I flew through those. I think I ended up getting a B for art, getting an A for English which was interesting. It helped me understand why I ended up going on in later years of my life to do a PhD. I write quite well and I just didn’t pursue that at the time, I pursued the act of making visual art.

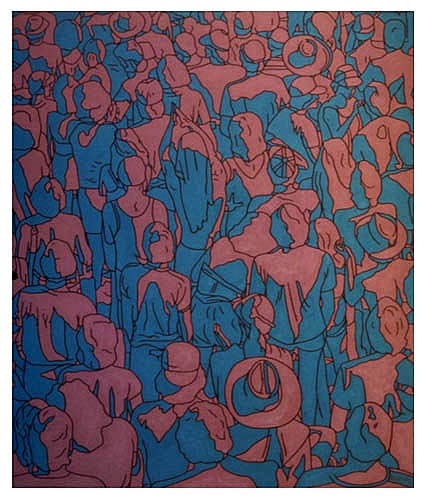

John Dahlsen “Mass Fallout” 1986

210 cm x 175 cm

It’s a similar thing that can be said about my movement into working as an environmental artist. In that I stumbled across that as well. I found myself collecting driftwood at a very southern location, a very remote location down at the corner of Victoria and NSW, where it was four-wheel drive only. I went down cliff faces and along beaches, kilometer’s along beaches, dragging back lumps of driftwood.

However I noticed there were plastics along the beaches, so I started cleaning that up and collecting. I ended up with around 60 to 80 jumbo garbage bags of stuff and I sent all of that back with all of my driftwood to Byron Bay. It was only because I moved into this new place in Byron Bay that had lime-washed walls and ceilings and I thought hmmm, wouldn’t that be nicely complimented by a series of driftwood furniture. So I went looking for the driftwood for furniture with my partner and I ended up getting all this plastic that was washing up. I collected wood to make furniture when I was at the Victorian College of the Arts and I made furniture then, but I didn’t even think of it as it as sculptural thing and if I had of shown some of the sculpture lecturers there what I had done, they probably would have said why don’t you get into doing this as sculpture, but I didn’t. I was very much attached to being a painter and I pursued that for 17 years before I stumbled across these plastics and things like that. So yes, that was an interesting journey. It was another one of these things of not planning things out and just kind of being creative with my life in general and I think that’s what artists generally do.

“Tree 2” 1982

260 cm x 340 cm

“The Pass #1” 2007

122 cm x 244 cm

“Julian Rocks” 2008

122 cm x 183 cm

JH: You become quite passionate when you start to talk about that these experiences of walking along the beaches and finding these objects, do you feel like you’re quite attached to the creative process?

JD: I absolutely love the process, I am passionate and I absolutely love that part of artr making and being in the studio and also getting out there in nature. I’m really into nature I exercise a lot. I do a lighthouse walk everyday in Byron Bay when I’m there. I ride my bike in the morning, I do barbells. I look after myself. I like to keep fit and I encourage my students and other artists to be like that. To take care of their bodies, to stay fit and vital so that, you know, they don’t just become old early, or just lethargic or obese.

JH: There is that association with artist’s and drug and alcohol abuse……

JD: Well I think with artists in general, we do like to look at things with an alternate reality. Van Gogh was very much into absinthe and that had a lot of, kind of, transformative qualities for the mind and would help with hallucinations and different things like this and also probably contributed to some of his illness in terms, of his mental illness. Which he just didn’t seem to deal with during his lifetime. I’m all for moderation of stuff you know.

JH: Do you think that’s the association, why you were interested in philosophy, philosophy’s all about looking at things from all perspectives, is it?

JD: Well it’s interesting that you say that because I was educated by the Jesuits. When I say I went to boarding school I went to a place called Xavier College in Melbourne. It’s a Catholic education and what they’re known for is getting you to argue from both sides,which is quite transformative, which was quite good for me because it helped me not to be rigid. I also say to people that I know and my students, the secret to staying young is by staying flexible on all levels, with your body, by doing yoga, and doing different things – staying moving, with your thoughts and with your opinions with your life, everything just to stay flexible.

JH: What advice you would give your younger self?

JD: I guess I would pat myself on the back and say you know you’re going to have a really enjoyable future. You’re going to have a great life, don’t worry, don’t freak out. You might have come from some adversities in earlier times in your life, when you lost your father at an early age, but you ended up with a great stepfather who was a wonderful man throughout your life and still is. So you know, you don’t need to be too sad. Just enjoy life and enjoy it to it’s full. You’re just going to have a great time and I’ve had a wonderful time. I’ve had a very alternative time. I spent a lot of time in India in ashram’s, I’ve had a very rich, rich life not a rigid life. I’ve come to teaching quite late in my life I suppose, I’ve had a whole career as an artist, a 30 year career as an artist. Suddenly I’m in academia where I’m teaching, but it’s the perfect time in my life to share what I’ve learnt. I can pass it on and I can give back and this is something that’s fantastic. I still make art, I’m about to start a whole new body of work in my studio in Byron bay. I’m really excited about that.

JH: What’s the new project?

JD: It’s interesting because I work with plastics that wash up on the beaches and I work with recycled plastic bags. I like to make statements about things. I also like to paint images of Byron Bay. There was recently an amazing storm that I saw in Byron, where the ocean turned pitch black and the storm came from one moment to the next. In this storm you could just see some light blue in the sky underneath these pitch black clouds and then you saw Julian Rocks out there in the ocean, and it’s all identifiable and the coast over here and I remember it so distinctly, I have a photographic memory, it was so impressive. I want to combine the use of recycled plastic bags and paint to be able to recreate these images on large canvas’s.

JH: Are they going to be flat or are they going to be 3D?

JD: It’ll be mainly flat but there will be some 3d elements. So that to me is a starting point, where it goes I’ve got no idea.

JH: One of your body of works is a series of paintings of the scenes around Byron Bay but they’re actually quite digital looking paintings.

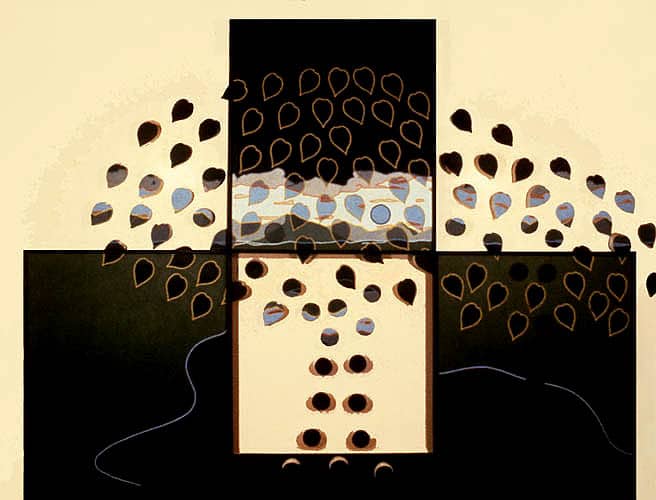

Blue Rope 2003

165cm x 44 cm

JH: I find it really interesting that you can move between all these different mediums and forms, you do it quite freely.

JD: Yes I give myself total permission. I don’t have a commercial gallery breathing down my neck saying John could you stop doing that or can you please, now that you’re painting beautiful paintings of Byron Bay, can you please just make lots of them. Or can you stop painting these landscape’s and go back to your plastic things cause your known for your plastic things.

I mainly show in museums these days. In international museums, I had a recent a show at the Anchorage Museum in Alaska and that travelled through United States to a number of other museums. That was part of a group show called “Gyre” and was all about the Garbage Patch in the Pacific and artists who use ocean litter plastics. So there were twenty of us from all over the world who participated in the show. I also show in regional galleries. I will be showing in Brisbane in the Buddhist Centre next year, they’ve got a beautiful big gallery out there. I’m not a Buddhist but I love Buddhism. Even though Buddha did say he didn’t want any sculptures or images made that people would adore. That’s what he said. Everybody’s got some in the garden these days that’s an interesting one. That show will be touring down to Sydney to the Buddhist University down there. It also has two major big galleries joined together and I’ll be showing there.

JH: Is the work associated with something that has reference to Buddhism?

JD: Well yes the work encourages in the viewer a sense of silence and meditation and it’s something that is very deliberate on my part. My PhD was all about environmental art, that’s the title of it. “Environmental Art” Activism, aesthetics and transformation. The transformation part was the one that invited the viewer into another space inside as they looked at the works. As they engaged with the work they could go into a state of meditation if they really got the works. Some people have said that without even knowing, they’ve said to me “your work is an invitation to meditation. You provoke people, you get their interest because of the materials you use. Which is tempered by the aesthetics you bring to it. So it’s quite beautiful even though you are using rubbish and at the same time, the trick is, what your doing is, your inviting them to meditate”. And I said wow, you really get the work. Because for me that’s really what it’s all about. I’m very aligned with the whole Buddhist nature and meditation, being silent and still inside. Still in the mind instead of walking around with a completely chattering mind. Being disturbed all of the time for some reason or another. The other thing is the Buddhist centre in Sydney is located on what used to be a dump. They’re totally excited about it, the whole centre is based on what used to be a refuse dump. I’m excited.

JH: Do you require a certain space to create, or to me you seem like your an artist who can create anywhere?

JD: Well, yes I like to be flexible. I’m about to go to Indonesia in June, the Australian Consulate is flying me over to do some workshops with Indonesian communities and with artists and university students. I’ll be delivering a keynote speech at a symposium over there also. Then running some workshops to basically teach these community members how to work with found objects, especially beach found objects. In this case I’m going to focus on Styrofoam, there’s Styrofoam washing up everywhere. Over my career I’ve made a lot of works with this medium. I’m quite excited to just isolate that as a material that I want to work with. This is mainly so I can keep a sense of aesthetics – I’m only there for a week. I’m in Bali for 3 days at a workshop and will be speaking at a seminar on “Waste to Wealth” then I’m going to Lombok for three days to do another seminar. I’ll be creating and donating a series of artworks for the Indonesian government give to the Indonesian Institute of Arts (ICI) over there.

Its going to be a really good thing and good things come of this kind of activity and ‘giving back’. I like to give back. I like to give up artwork up for auctions I like to donate artworks to institutions. I’m at a point in my life where I can do that. When I was younger I couldn’t afford to. Now I can. I’m not asking for a fee, I’m just doing it and it’s going to be a really wonderful thing. I will have an exhibition this time which will lead to a larger exhibition that will travel through SE Asia.

JH: So what advice would you give somebody who was a younger artist, looking to continue on with their art, maybe do some projects similar to yours or follow down a similar path?

JD: I think probably I would start with something very simple. Keep saying yes, learn how to say yes. I find as younger people tend to be a little bit more measured and they’ll often way up their choices, sometimes saying, they’re not sure whether they can do this because of self -doubt or, whatever it is. I say just jump in and say yes just workout the difficulties later. If you say no to something or seem hesitant you’ll miss out on the opportunity. I’m a big yes sayer, just deal with it later if you can’t end up doing it or figuring it out and it’s just not possible whether alone or with other people, just deal with that later.

And also look after your health. I say for anybody as a young person there’s a temptation to just give yourself, your body, a really hard time. I did so I know from experience. Also just take care of your health, and the earlier that you do that the better and don’t be scared of making money. I say that, I’ve written a book about it, it’s called “An Artist’s Guide to a Successful Career” – Strategies About Financial and Critical Success. That’s what the book is all about, how to be an artist, the business of being an artist. Often I’ve heard, so many times, artists going through art school and they were never told the business of being an artist, how to arrange your finances, what happens if you have a big sell out at a show? Do you just squander that money, or do you start a little portfolio, buy a property buy a flat or a unit something? Start the process of managing your money wisely so you can enjoy wealth. l, and a lot of artists I know do this. I also confront my students about this all the time. What is your attitude to art and money? If you were to be successful would you have the attitude “everybody is going to think I’ve sold out”, for example that sort of thing, and to ask yourself, what is my attitude, how do I price my art? All these different things and I can tell you a little secret right here. The National Association of Visual Arts (NAVA), have a very clear document that they freely give out and it is basically the amount per hour at different stages of your career, as an artist you should be asking for, every hour you put into your work in order to be able to come up with a number. If you have a canvas and it takes you 10 hours to do or 20 hours to do, and your’e basing the figure and your position at that moment, midway through a degree, and that’s very early career, you‘re looking at $23.50 an hour. A lot of artists don’t want to put that together, you know, saying “what about the inspiration” or “I can’t charge that much” and they forget about putting a price on the actual materials first, you get that and, then you get the hours spent. A lot of artists put ridiculous prices on things because they get all emotional, and say “that’s my baby I don’t want to let it go”.

So this is the sost of thing I also engage myself in as a lecturer and author.

JH: What’s one place in the world you think every artist should see?

JD: Ok I tend to be a fairly traditional with that I would say, India for sure… I’m only kidding because I said New York the other day.

India is so full of color and so full of laughter and joy and extreme poverty and some ridiculously bad things going on, with people smuggling and all sorts of different things. It’s a place of tremendous heart. You go there and you feel like “oh, I‘ve come home” you don’t know why. It’s really rich, the food is unbelievable.

As something to do, it’s a little bit like going to mecca. Go to New York! Go and spend some time at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MET) in New York. Have lunch there with a friend and go to the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) and the Whitney and a few things like this and just spend a week there. Go to Chelsea and some places like this, go to some of the commercial galleries and just see what’s rocking. Also Berlin. There’s some very exciting things happening there.

JH: Many thanks to John Dahlsen for the interview.